Life in Afghanistan

15/08/2012 - present

|

It is amazing how fast life can change, and how unpredictably. For me this meant going from life on the open road – three years of no commitments, hitchhiking, a backpack and a tent – to a life that my friends and family refer to as “domesticated” (I hate that word) – house, dog, cat, job and long term relationship. Looking back it seems to have happened overnight: one morning riding yaks through the Wakhan corridor with plans to hitch Central Asia and cross Mongolia on a horse, the next in the big city with a job offer that included so many benefits, plus the excitement of Afghanistan (the country grew on me unexpectedly and quickly) I could hardly turn it down.

|

|

I had never planned to stay in Afghanistan, actually it wasn’t even on my original route. After a month and almost 200 euro I had managed to get an elusive Uzbek visa stamped into my passport. The original plan was to head there quickly through Turkmenistan, but the transit visa for that political nightmare of a country seemed difficult to obtain, and IF they issued it then it would be for a maximum transit time of 5 days. I’m simply not a fan of rushed travel. The solution came one day while driving with my Couchsurfing host in Teheran. The huge Afghan flag waving in the air seemed to beckon me towards the embassy, and upon enquiring I learned that the Afghan visa was both cheap and issued overnight – I’d found my solution. After passing the rest of my time in Iran hopping cross country with my ever-traveling friend Edrin, I hit the road hitching east to the forbidden border.

I would say that the fast-paced life and the idea that something could explode at any minute were the original factors that attracted me to Afghanistan, but what got me to take the job I was offered (besides the salary and ridiculous benefits) was that I would be working with all Afghans, visiting U.S. military bases, and traveling in a way most foreigners do not get a chance to. The job I was offered was marketing manager (officially C.O.O.) of an Afghan construction company doing military contracting. For the last ten years it was easy to make money doing contracting – the American military was practically throwing it at Afghan companies as part of their “Afghanistan reconstruction” policy. Recently, however, Americans have been pulling back, and the cow that made so many Afghans fat and rich is starting to run dry. My boss was one of these typical Afghans; he had been a poor worker – a crane operator I have heard – until he pulled together enough money to get a business license and start his own company. With the Americans being so lax with handing out projects to anyone (in the beginning), my boss starting winning projects. Although he was illiterate and had little more than a computer, and certainly no office or the finance to back his project bids, he had the Afghan businessman in his blood and with clever partnerships (and many backstabbings) he was able to grow his company and became quite wealthy. They hired me because as the American money dries up, competition gets stiff, and having a foreigner, especially a woman, representing your company is a huge step up.

|

So much time has passed since I first arrived in Herat until now that I can’t possibly fill in this blog with as much detail as I would have liked – I should have been writing the whole time but somehow being stationary I just don’t get the same inspiration as I do when I am on the road. But I should have written. The fact is that being stationary in a place like this means that besides all the interesting things to say from a traveler’s point of view, there are also tons of personal yet highly interesting and culturally relevant details I could fill in that give a lot of insight into life here. I’ll do my best to sum it up in this, and possibly subsequent, blog entries.

|

|

As I said, I will not go into too many details here. But I will mention some of the highlights that got me so hooked on the country. First, I loved being a free expat. The majority of other foreigners living in Kabul are locked behind high walls and cannot even go out on their own to buy bread next door – they only travel with high security including armored vehicles, bullet-proof vests and armed guards. When I got my own car, and eventually motorcycle, one of my favorite pass times became chasing down these armored convoys and waving at the foreign guards inside. Most of them were shocked, others irritated. I think many of the seasoned warzone veterans thought (and still do think) that I am young, niave and a stupidly obvious target. Personally, I think they make a much more obvious target than I do. From my experience, which even surprised me, Afghans are extremely friendly to me when I drive. Other drivers give me the right of way, women wave constantly, and many of the policemen who are used to seeing me zipping around on my bike will stop traffic for me. Its amazing how friendly people are. Some of my favorite reactions come from the friendly women who love seeing another women on the road. My best memory was of a woman in burqa walking up to me while I was stopped in traffic, patting me on my back and giving me the thumbs-up sign. Amazing.

|

When I started I did not even know the difference between an excavator and a grader, but I didn’t need to. All I needed to do was drive through Taliban country disguised in a burqa and show up at a military base in a car (as opposed to the helicopters taken by other civilian foreigners). This in itself was so shocking for the U.S. contracting officers that they generally became too caught up buying me coffee and talking about traveling than discussing boring details about water tank specifications and building CMU walls. Can’t blame them either, life on those bases seems boring as hell (except for the daily rocket attacks from surrounding Taliban mountains, that spices things up a little). Anyway, in exchange for these kinds of trips (which I loved - how else would I be able to visit places like Maidan-Shah Wardak and Lowgar province?) I was given a huge house filled with furniture that I got to pick out myself (right down to the kitchen knives), a new model car (I declined the driver), all expenses paid from restaurant and grocery bills to gas for the car, and even all-expenses paid trips to Dubai and the States, not to mention an untaxed salary that I thought was huge (although I later found out that it was quite a bit less than what the average foreigner makes). I figured I would work there for a while, save some money so I could afford my Mongol horse, then continue on my way. Little did I know just how strong of a hold Afghanistan would take on me.

|

|

As far as my career path goes it became clear very quickly that although good for my savings account, the sleazy, scheming underworld that is contracting in Afghanistan definitely was not for me. It was interesting to learn just how low people (Afghan and American) can go for money and image – how easy it is to throw out money for bribes, find a scapegoat, or stab a business partner in the back and steal his share of funds. Not to mention that the players themselves in that industry are the sleaziest I’ve ever met – most of them are alcoholics and many are meth addicts, and the stories of prostitution at its very lowest and most violent show just how messed up the fundamentals of the Afghan male mind have become after 30+ years of war. I wont go into a rant about bachabazi here, but look it up if you are interested in the dark side of this country.

|

I also enjoy living outside the compound life because it has meant Ive had a lot of freedom to travel the country. Road trips to Jalalabad, Panjshir, Mazar, Wardak, Lowgar, Badakshan, and everywhere in between has allowed me to keep a feeling a freedom and exploration which I could not live without. My burqa has proved extremely useful for these travels – I’ve learned to hunch down in the backseat and try not to look around too much in order to imitate an Afghan woman – so far so good, although those things are hot as hell in the summer.

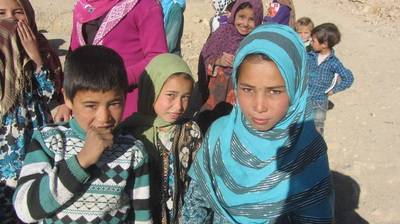

Lucky for me, just as my construction work was falling through a friend introduced me to the director of an NGO that needed a website designed. This turned into a life-changing career opportunity. Working at PARSA has been an incredible experience, not only have I learned an incredible amount about how a small scale independent NGO operates, I’ve also learned a lot about how the industry works. And I couldn’t have asked for a better NGO than PARSA. Founded in 1996 PARSA is one of the only foreign organizations that operated in-country throughout the Taliban regime. Even when the then-director was arrested for employing women, operations continued. Our projects are varied, but our main focuses are on empowering women economically, helping improve the psychosocial situation of the communities we work in, and children’s programs – namely the Afghan Scouts. The perspective I have gained while working at PARSA is what has given me a deep love and connection to its people – particularly its women – and what will keep me connected to Afghanistan for many years to come.

|

That is all I will include for now. As I reread this I realize how sporadic and incomplete it is, but it is just some thoughts that have been going through my head now that I am (temporarily) on the road again. I was meant to get another Afghan work visa in my passport, but a previously unheard of work visa rule, coupled with PARSA’s commitment to principals and refusal to pay bribes, meant that instead of stamping a work visa in my passport they stamped an exit visa which gave me six days to leave the country. I opted to head somewhere with a lot of green, and a lot of water, and ended up in SE Asia for a five week back-on-the-road adventure. It is nothing like my previous travels, far less adventurous and much more touristic, but it is a welcome breather from Kabul life and it feels so great to be on the side of a road with my thumb out again. Let me hear what you all have to say about his entry and I’ll think about whether to write more about Kabul. Hope you are all well, keep in touch!